Creativity is “paintless” because the real work is invisible

People imagine creativity as a quick spark: a designer draws something, a marketer writes a line, and a new idea appears.

In reality, creativity is often a paintless process: no visible output for hours (or days), but a lot of internal work.

The inconvenient truth is that good ideas need:

- time (for iteration and incubation)

- focus (to hold constraints in working memory without distraction)

- procedure (a repeatable way to explore, test, and refine)

And sometimes the best move is to stop trying — and go to sleep with “opened eyes,” meaning: let the brain keep searching while you rest. It may feel like nothing is happening, but often creative people wake up the next morning with an excellent solution or idea.

“The most dangerous myth about creativity is that it should be fast.”

Focus is the fuel

Why “just try harder” fails when your attention is fragmented

Creative work is demanding because you’re holding many constraints at once:

- the brief

- audience expectations

- brand tone

- hierarchy, typography, rhythm

- technical limitations (sizes, formats, channels)

If you constantly switch tasks, you don’t just lose time — you lose the mental state that carries the problem forward.

Research on “attention residue” suggests that after switching away from a task, part of your attention remains stuck on the previous one, reducing performance on the next.

That’s why “30 minutes of design between meetings” can feel like “no progress,” even if you were working the whole time.

If you want more on where good ideas tend to appear outside the desk, see Where Do Designers Find Inspiration?.

If you want an honest measure of creative productivity, track uninterrupted time blocks, not hours logged.

The hidden stages: why creativity rarely starts with “illumination”

Wallas’ model still matches modern creative work

Graham Wallas described four stages that show up again and again in real creative projects:

- Preparation — research, constraints, references, drafts, collecting raw material

- Incubation — stepping away while the mind keeps recombining pieces

- Illumination — the “aha” moment (often brief)

- Verification — the long phase: editing, testing, polishing, rejecting 90%

Most people only notice stage 3.

Professionals live in stages 1 and 4.

If your process doesn’t include a deliberate “verification” stage, you’re not missing creativity — you’re missing craft.

Why “come on guys, let’s create something in 10 minutes” fails

Brainstorming often produces more ideas and worse ideas

Group brainstorming is popular because it feels energetic and social. But research on brainstorming groups shows persistent problems:

- production blocking: only one person can speak at a time, others forget or self-censor

- evaluation apprehension: people avoid “weird” ideas in front of the group

- social loafing: responsibility diffuses; effort drops

In classic experimental work, nominal groups (people working alone, then combining ideas) tend to outperform interacting brainstorming groups in both quantity and quality.

“If you want better ideas, separate “idea generation” from “idea discussion.””

Solo first, small circle second

The practical compromise that many studios already use

There’s a pattern that repeats in design, writing, and strategy:

- Solo creation produces the raw material (bold, unfiltered, fast exploration).

- Small-team critique improves it (clear constraints, sharp feedback, quick decisions).

Large-group creativity sessions often become:

- performance

- politeness

- consensus-building

And consensus is rarely the same thing as originality.

The science of “sleep with opened eyes”

Incubation is not laziness — it’s a cognitive strategy

When you step away from a problem, your mind doesn’t fully stop working.

In studies of the incubation effect, breaks often improve performance on creative or insight problems — especially when the task requires remote associations rather than linear calculation.

Sleep can amplify this effect.

If you want the “step away” idea grounded in attention and stress research, read Designers and Nature: Is the Outdoors a Quiet Institution of Creativity?.

Research on sleep and problem solving suggests that sleep supports:

- memory consolidation (storing useful fragments)

- recombination (connecting distant ideas)

- reduced fixation (loosening the grip of the wrong approach)

This is why a solution that didn’t arrive at 11:30 PM sometimes appears at 7:10 AM, almost finished.

Try this: write down the problem before sleep in one sentence, plus three constraints. In the morning, don’t check your phone for 10 minutes — sketch first.

When great ideas don’t come: fixation, saturation, and the “wrong hill”

The block is sometimes a signal, not a failure

There are days when the mind produces nothing but repetitions.

This is often not a lack of talent — it can be fixation: getting stuck on the first plausible approach and unconsciously circling it.

A useful pattern is to treat blocks as diagnostics:

- If you feel stuck quickly, you may be missing material (more references, more research, more constraints).

- If you feel stuck after many drafts, you may be missing direction (the brief is ambiguous, the target is unclear).

- If you feel stuck late at night, you may be missing recovery (sleep, food, a walk, a hard stop).

In practice, “go to sleep with opened eyes” means you stop forcing the solution — but you keep the problem alive in a simple form your brain can keep chewing on.

If what you’re feeling is “I used to be creative, now I’m empty,” this may help: Is Creativity Endless, or Can Designers Run Out of it?.

A procedure that makes creativity repeatable

“Process” doesn’t make work robotic — it creates room for luck

Creativity improves when you reduce the number of decisions that steal attention.

A simple, repeatable procedure protects deep focus:

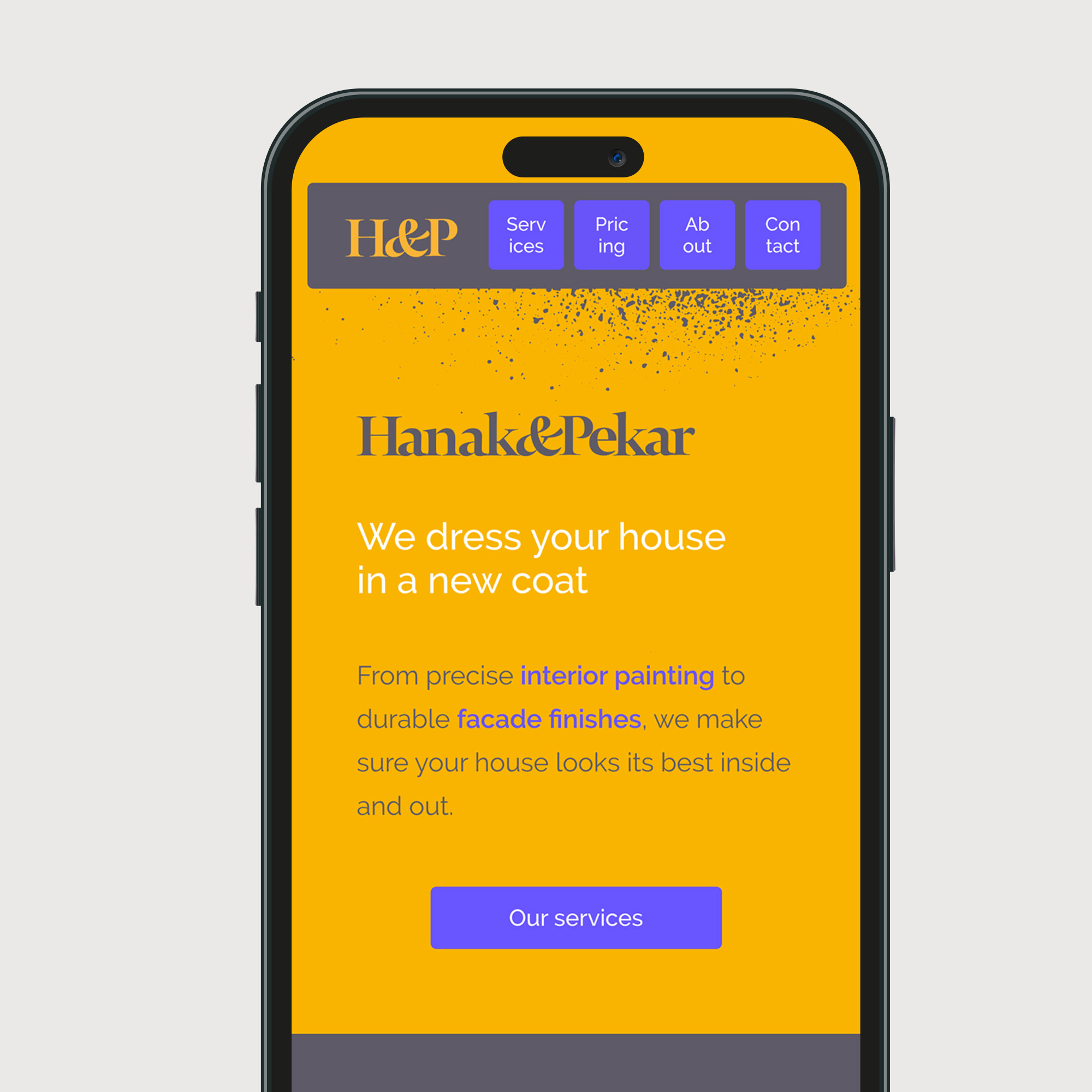

1) Define constraints like a designer, not like a manager

Bad constraint: “Make it modern.”

Useful constraint: “Single symbol, works in 16px, two colors max, recognizably ours in 2 seconds.”

2) Build a “material library”

Creativity is recombination. Give yourself material to recombine:

- competitor scans

- typography samples

- packaging photos

- copy headlines

- textures, shapes, UI patterns

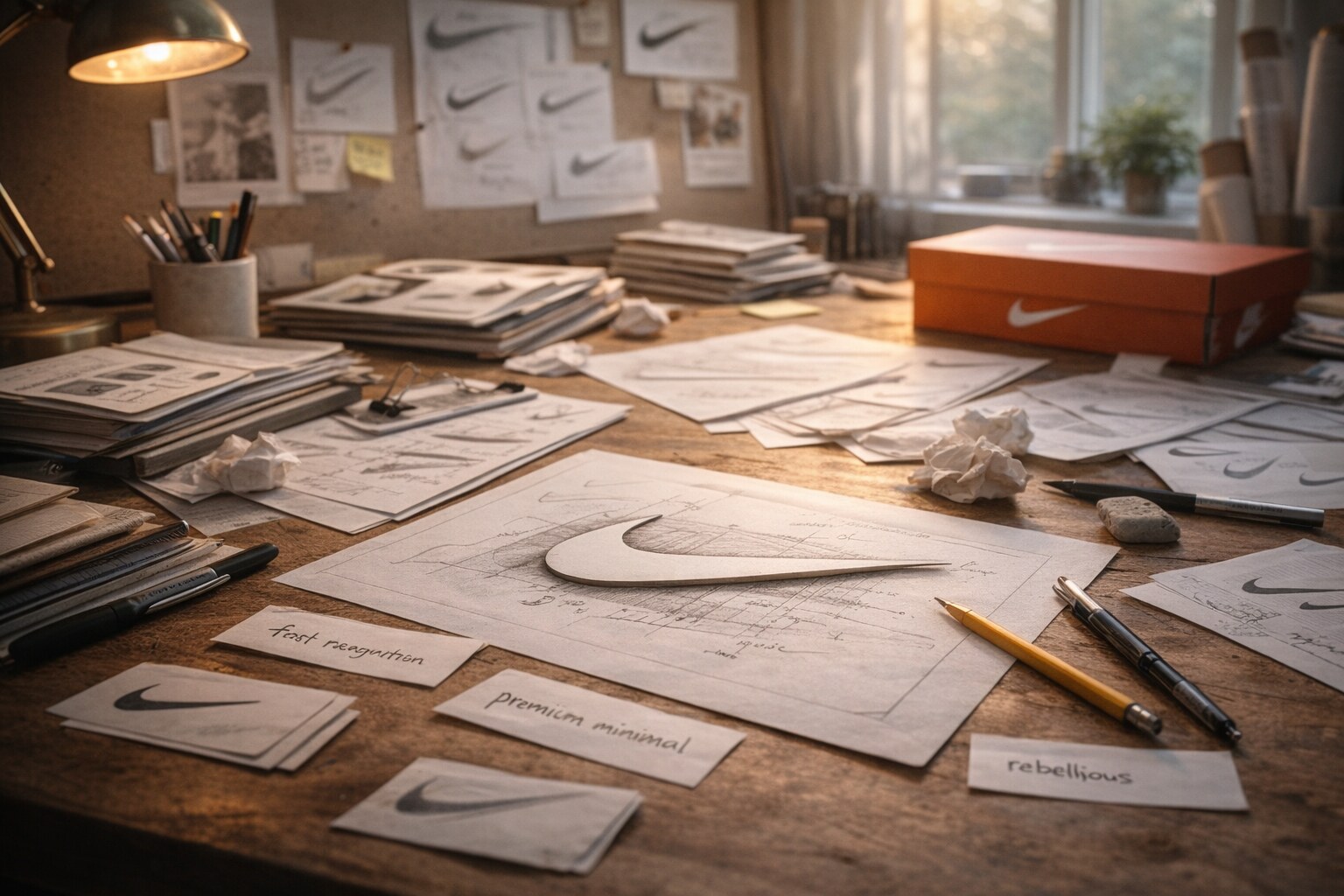

3) Generate privately, then label what you made

Don’t judge ideas while generating them.

Afterward, label each draft with a purpose:

- “fast recognition”

- “premium minimal”

- “rebellious”

- “friendly utility”

This turns “taste” into a searchable system.

4) Critique in a small circle with rules

Use rules that prevent vague feedback:

- critique must reference a constraint

- propose a fix, not just a dislike

- keep it to 20 minutes

If you still want group input early, use a structure that avoids “loudest voice wins”:

- brainwriting: everyone writes/sketches silently for 5–10 minutes, then swap and build

- gallery critique: pin 10–20 drafts, vote silently, then discuss only the top 3

5) Ship a version and learn

Verification is not only internal polish — it’s reality-testing:

- A/B test the message

- show five people the design for 3 seconds, ask what they remember

- print it small and look from distance

Legendary stories

Iconic work is rarely born from “instant creativity”

The Nike Swoosh: one student, one simple shape, a lot of iteration

The Swoosh is often treated like a magical stroke.

The real lesson is less romantic: a single designer (Carolyn Davidson) explored options, presented variants, and the final mark survived because it worked at speed, scale, and motion.

One detail many people miss: early on, this kind of work can be undervalued and underpaid — and only later becomes “legendary.”

I ♥ NY: a sketch that became infrastructure

Milton Glaser’s “I ♥ NY” is famous partly because it looks effortless.

But what made it powerful wasn’t the sketch — it was the constraint: instant meaning, minimal elements, and high reproducibility across media.

The FedEx arrow: a hidden idea that rewards attention

The negative-space arrow in the FedEx logotype shows what typographic refinement can do.

The mark works even if you never notice the arrow — and becomes stickier once you do.

The lesson isn’t “try harder in a meeting.” It’s: spend time aligning geometry, spacing, and letterforms until meaning appears.

“Think Small”: the ad that proved constraints can be a creative superpower

Volkswagen’s “Think Small” campaign is remembered because it did the opposite of what advertising pressure usually demands.

Instead of loud claims, it used clarity, honesty, and restraint — which made it feel intelligent and trustworthy.

This is a creativity pattern designers recognize immediately:

when you remove the need to impress everyone, you get room to be precise.

The Nike tagline “Just Do It” feels like something a team could shout out in a room.

But what made it powerful was not cleverness — it was fit: it matched a cultural moment, a brand ambition, and a simple internal standard for decisions.

Many legendary lines survive because they become tools inside a company: they guide choices long after the campaign ends.

“Iconic design often feels simple because complexity was removed, not because it never existed.”

Similar ideas, different angles

Conclusion

Creativity is not a meeting — it’s a time-based craft

Creativity isn’t paint on a canvas. It’s a focused process that happens before the visible output:

- gather and define constraints

- generate privately without shame

- step away to incubate (often sleep helps)

- return to verify, edit, and compress

- discuss in small circles, not crowds

If your team wants better ideas, don’t schedule “creativity.”

Schedule time, solitude, and a disciplined critique loop — and let the “spark” arrive when your brain has earned it.