Graphic Design in the 19th Century

How it was made before “design” existed. Graphic design—printing methods, poster culture, typography trends, and the real production workflow behind Victorian-era visuals.

How it was made before “design” existed. Graphic design—printing methods, poster culture, typography trends, and the real production workflow behind Victorian-era visuals.

The 19th century is where “graphic design” (as we think of it today) quietly takes shape—without the title, without software, and often without a single person owning the whole composition.

It was a world of compositors, engravers, lithographers, type founders, and printers—all contributing to what we’d now call layout, typography, branding, and visual communication.

If the 20th century invented modern design studios, the 19th century invented the industrial pipeline that made design scalable.

In the 1800s, the job title graphic designer didn’t exist (the term becomes common much later). But the work absolutely did:

The big difference: the “designer” was often a craft specialist inside the print ecosystem, not a single author controlling everything end-to-end.

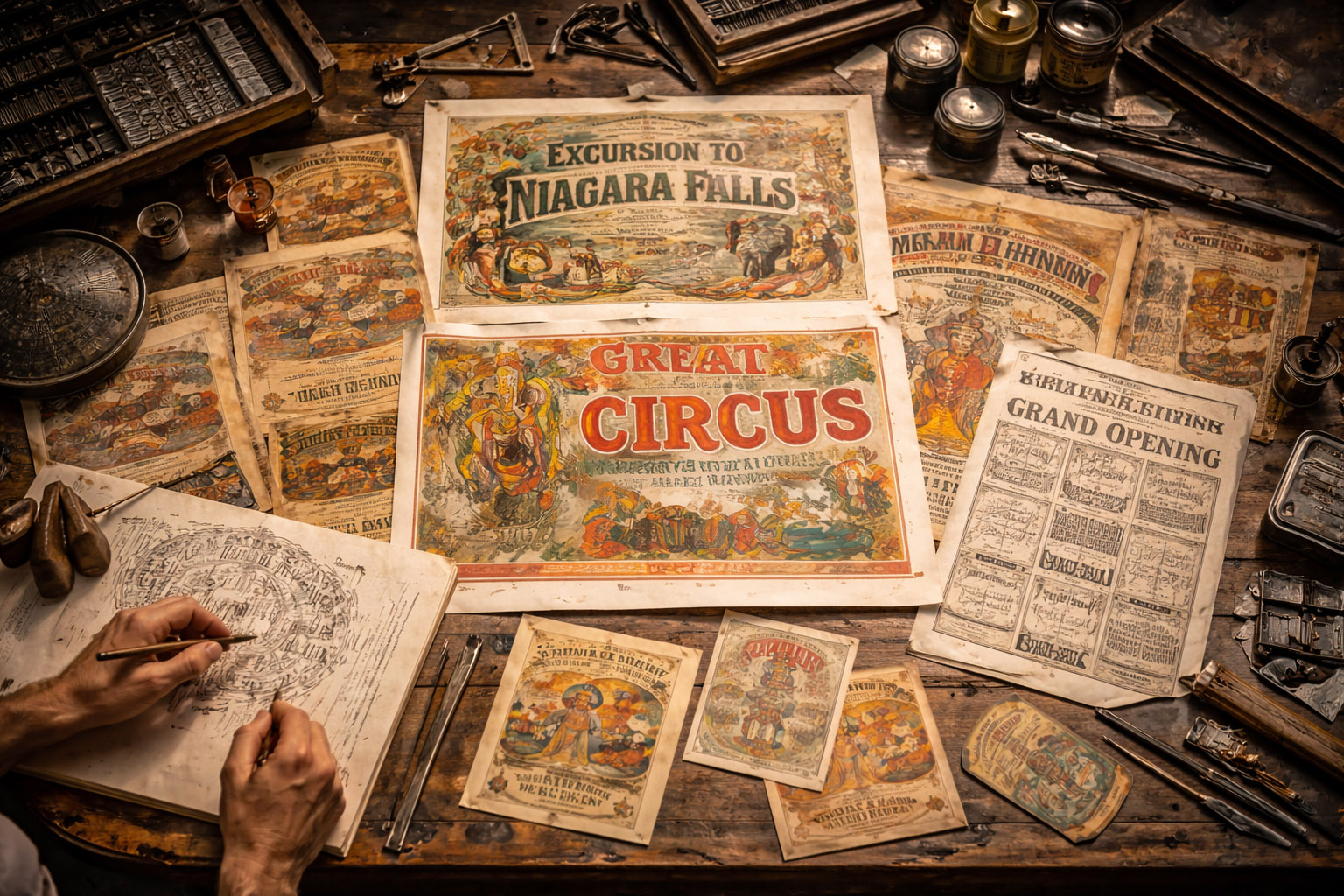

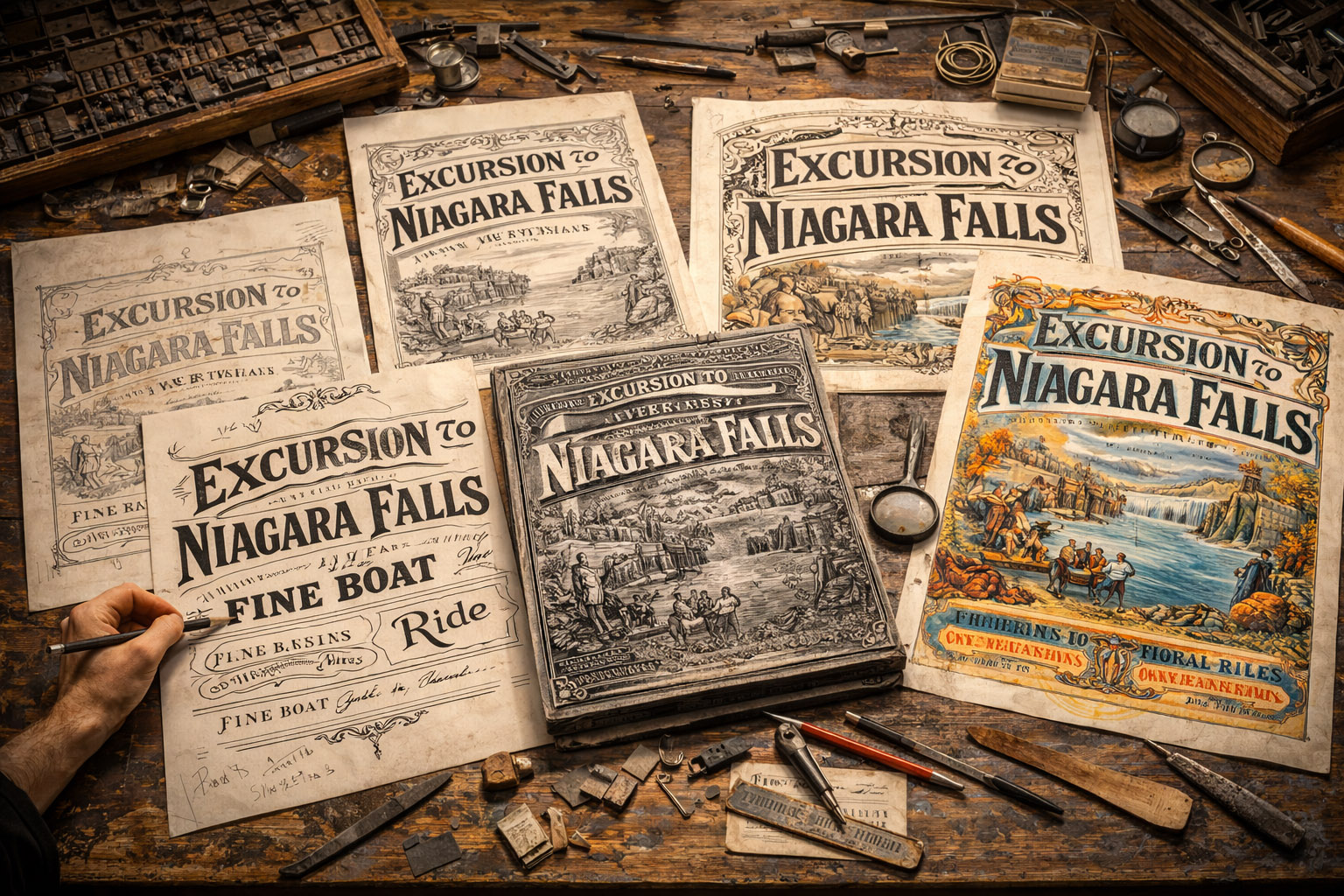

Reality check: a single poster could pass through multiple hands—one person drawing, another letterforming, another making plates/stones, another printing, another finishing. What we call “design” was distributed labor.

As presses became faster (and paper production scaled up), print stopped being a luxury object and became a mass communication channel. That shift created demand for:

Lithography (printed from a flat surface—traditionally stone) was a turning point because it let artists create:

Unlike metal type, lithography could reproduce expressive strokes and painterly textures with fewer compromises.

Color printing grew into a competitive advantage. Chromolithography required separate stones/plates per color, carefully registered so every layer landed in the right place.

This pushed print toward what we’d now call production design:

Less-known production trick: many color prints used a strong dark “key” layer to anchor details. If colors drifted slightly, the image still looked sharp because the key line held it together.

Before photo reproduction became easy, newspapers often relied on wood engravings to translate events into images. Sometimes these were made from photographs—but the photo couldn’t be printed directly, so an engraver converted it into a printable pattern.

In the late 1800s, halftone screens (printing images as dot patterns) helped unlock mass photo reproduction. That change slowly reshaped editorial design:

Hot-metal typesetting (Linotype and later systems) compressed the time between writing and printing—pushing periodicals, ads, and catalogs into a faster cycle. More pages, more ads, more competition—so visual hierarchy mattered more than ever.

When advertising explodes, typography becomes a battleground. The 19th century is famous for:

This is why Victorian prints often look “busy”: they were competing for attention in a dense visual market—shop windows, streets, newspapers, handbills.

If social media today is a scroll of competing visuals, the 19th-century city wall worked similarly:

Lithographic poster artists helped define what “modern” looked like before modernism:

Unknown-but-important shift: posters weren’t only “art”—they were an early laboratory for conversion design. The question wasn’t “is it beautiful?” but “will it stop someone walking past?”

Here’s what the pipeline often looked like for a poster, label, or certificate:

The “design system” wasn’t a Figma file. It was repeatable print components: borders, ornaments, type combinations, and standard page structures.

19th-century graphic design was the birth of design-as-industry: mass print, mass advertising, and the rise of visual competition. It wasn’t clean or minimal—but it was highly strategic, deeply crafted, and surprisingly modern in its intent.

“Before “graphic design” had a name, it already had a job: make information readable, persuasive, and repeatable—at scale.”

News, insights, case studies, and more from the rausr team — straight to your inbox.

Send us your brief, your wildest idea, or just a hello. We’ll season it with curiosity and serve back something fresh, cooked with care.